Hera

Hera, probably identical with kera, mistress, just as her husband, Zeus, was called ἔρρος (erros) in the Aeolian dialect.1 The derivation of the name has been attempted in a variety of ways, from Greek as well as oriental roots, though there is no reason for having recourse to the latter, as Hera is a purely Greek divinity, and one of the few who, according to Herodotus,2 were not introduced into Greece from Egypt.

Hera was, according to some accounts, the eldest daughter of Cronus and Rhea, and a sister of Zeus.3 Apollodorus,4 however, calls Hestia the eldest daughter of Cronus; and Lactantius5 calls her a twin-sister of Zeus. According to the Homeric poems,6 she was brought up by Oceanus and Thetis, as Zeus had usurped the throne of Cronus; and afterwards she became the wife of Zeus, without the knowledge of her parents. This simple account is variously modified in other traditions.

Being a daughter of Cronus, she, like his other children, was swallowed by her father, but afterwards released,7 and, according to an Arcadian tradition, she was brought up by Temenus, the son of Pelasgus.8 The Argives, on the other hand, related that she had been brought up by Euboea, Prosymna, and Acraea, the three daughters of the river Asterion;9 and according to Olen, the Horae were her nurses.10 Several parts of Greece also claimed the honor of being her birthplace; among them are two, Argos and Samos, which were the principal seats of her worship.11

Her marriage with Zeus also offered ample scope for poetical invention,12 and several places in Greece claimed the honor of having been the scene of the marriage, such as Euboea,13 Samos,14 Cnossus in Crete,15 and Mount Thornax, in the south of Argolis.16 This marriage acts a prominent part in the worship of Hera under the name of ἱερὸς γάμος (hieros gamos); on that occasion all the gods honored the bride with presents, and Gaea presented to her a tree with golden apples, which was watched by the Hesperides in the garden of Hera, at the foot of the Hyperborean Atlas.17

The Homeric poems know nothing of all this, and we only hear, that after the marriage with Zeus, she was treated by the Olympian gods with the same reverence as her husband.18 Zeus himself, according to Homer, listened to her counsels, and communicated his secrets to her rather than to other gods.19 Hera also thinks herself justified in censuring Zeus when he consults others without her knowing it;20 but she is, notwithstanding, far inferior to him in power; she must obey him unconditionally, and, like the other gods, she is chastised by him when she has offended him.21 Hera therefore is not, like Zeus, the queen of gods and men, but simply the wife of the supreme god. The idea of her being the queen of heaven, with regal wealth and power, is of a much later date.22 There is only one point in which the Homeric poems represent Hera as possessed of similar power with Zeus, viz. she is able to confer the power of prophecy.23 But this idea is not further developed in later times.24

Her character, as described by Homer, is not of a very amiable kind, and its main features are jealousy, obstinacy, and a quarreling disposition, which sometimes makes her own husband tremble.25 Hence there arise frequent disputes between Hera and Zeus; and on one occasion Hera, in conjunction with Poseidon and Athena, contemplated putting Zeus into chains.26 Zeus, in such cases, not only threatens, but beats her; and once he even hung her up in the clouds, her hands chained, and with two anvils suspended from her feet.27 Hence she is frightened by his threats, and gives way when he is angry; and when she is unable to gain her ends in any other way, she has recourse to cunning and intrigues.28 Thus she borrowed from Aphrodite the girdle, the giver of charm and fascination, to excite the love of Zeus.29 By Zeus she was the mother of Ares, Hebe, and Hephaestus.30

Properly speaking, Hera was the only really married goddess among the Olympians, for the marriage of Aphrodite with Ares can scarcely be taken into consideration; and hence she is the goddess of marriage and of the birth of children. Several epithets and surnames, such as Eileithuia (Εἰγείθυια), Gamelia (Γαμηλία), Zugia (Ζυλία), Teleia (Τελεία), etc., contain allusions to this character of the goddess, and the Eileithyiae are described as her daughters.31

Her attire is described in the Iliad;32 she rode in a chariot drawn by two horses, in the harnessing and unharnessing of which she was assisted by Hebe and the Horae.33 Her favorite places on earth were Argos, Sparta, and Mycenae.34

Owing to the judgment of Paris, she was hostile towards the Trojans, and in the Trojan war she accordingly sided with the Greeks.35 Hence she prevailed on Helios to sink down into the waves of Oceanus on the day on which Patroclus fell.36 In the Iliad she appears as an enemy of Heracles, but is wounded by his arrows,37 and in the Odyssey she is described as the supporter of Jason. It is impossible here to enumerate all the events of mythical story in which Hera acts a more or less prominent part; and the reader must refer to the particular deities or heroes with whose story she is connected.

Hera had sanctuaries, and was worshiped in many parts of Greece, often in common with Zeus. Her worship there may be traced to the very earliest times: thus we find Hera, surnamed Pelasgis, worshiped at Iolcos. But the principal place of her worship was Argos, hence called the δώ̀μα Ἡρας (dōma Hēras).38 According to tradition, Hera had disputed the possession of Argos with Poseidon, but the river gods of the country adjudicated it to her.39

Her most celebrated sanctuary was situated between Argos and Mycenae, at the foot of Mount Euboea. The vestibule of the temple contained ancient statues of the Charites, the bed of Hera, and a shield which Menelaus had taken at Troy from Euphorbus. The sitting colossal statue of Hera in this temple, made of gold and ivory, was the work of Polycletus. She wore a crown on her head, adorned with the Charites and Horae; in the one hand she held a pomegranate, and in the other a scepter headed with a cuckoo.40

Her worship was very ancient also at Corinth,41 Sparta,42 in Samos,43 at Sicyon,44 Olympia,45 Epidaurus,46 Heraea in Arcadia,47 and many other places.

Respecting the real significance of Hera, the ancients themselves offer several interpretations: some regarded her as the personification of the atmosphere,48 others as the queen of heaven or the goddess of the stars,49 or as the goddess of the moon,50 and she is even confounded with Ceres, Diana, and Proserpina.51 According to modern views, Hera is the great goddess of nature, who was every where worshiped from the earliest times. The Romans identified their goddess Juno with the Greek Hera.

❧

The name might also come from the Greek haireo, "chosen one."

Iconography

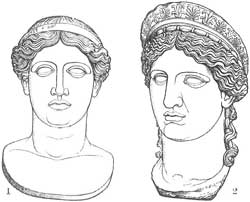

We still possess several representations of Hera. The noblest image, and which was afterwards looked upon as the ideal of the goddess, was the statue by Polycletus at the temple of Hera at Mycenae (ca. 415 BCE). She was usually represented as a majestic woman at a mature age, with a beautiful forehead, large and widely opened eyes, and with a grave expression commanding reverence. Her hair was adorned with a crown or a diadem. A veil frequently hangs down the back of her head, to characterize her as the bride of Zeus, and, in fact, the diadem, veil, scepter, and peacock are her ordinary attributes. She appears veiled on a frieze at the Parthenon (School of Phidias, ca. 435 BCE).

On Samos many representations of the goddess have been found, such as on coins. A sanctuary was discovered at Paestum in southern Italy, containing many votive offerings, among which statuettes of Hera seated on a throne holding a child on her left arm and a pomegranate in her right hand. In the twelfth century a church in the vicinity of this sanctuary was dedicated to the Madonna with the pomegranate. The Madonna and Hera appear identical.

References

Notes

- Hesychius, s.v.

- ii, 50.

- Homer. Iliad xvi, 432; comp. iv, 58; Ovid. Fasti vi, 29.

- The Library i, 1.5.

- i, 14.

- Iliad xiv, 201 ff.

- Pseudo-Apollodorus, l.c.

- Pausanias. Description of Greece viii, 22.2; Augustine. De Civitate Dei vi, 10.

- Description of Greece ii, 7.1 ff.; Plutarch. Symposiacs iii, 9.

- Description of Greece ii, 13.3.

- Strabo. Geography, 413; Description of Greece vii, 4.7; Apollonius Rhodius. Argonautica i, 187.

- Theocritus, xvii, 131 ff.

- Stephanus of Byzantium, s.v. Karustos.

- Lactantius. De Falsa Religione i, 17.

- Diodorus Siculus, v, 72.

- Scholiast on Theorictus, xv, 64; Description of Greece ii, 17.4, 36.2.

- The Library ii, 5.11; Servius on Virgil's Aeneid iv, 484.

- Iliad xv, 85 ff.; comp. i, 532 ff; iv, 60 ff.

- ibid. xvi, 458; i, 547.

- ibid. i, 540 ff.

- ibid. iv, 56; viii, 427, 463.

- Hyginus. Fabulae, 92; Ovid. Fasti vi, 27; Ovid. Heroides xvi, 81; Eustathius on Homer, p. 81.

- Iliad xix, 407.

- Comp. Strabo. Geography, 380; Apollonius Rhodius, iii, 931.

- Iliad i, 522, 536, 561; v, 892.

- ibid. viii, 408; i, 399.

- ibid. viii, 400 ff., 477; xv, 17 ff; Eustathius on Homer, p. 1003.

- ibid. xix, 97.

- ibid. xxiv, 215 ff.

- ibid. v, 896; i, 585; Homer. Odyssey xi, 604; Hesiod. Theogony, 921 ff. Pseudo-Apollodorus. The Library i, 3.1.

- Iliad xi, 271; xix, 118.

- ibid. xiv, 170 ff.

- ibid. iv, 27; v, 720 ff.; viii, 382, 433.

- ibid. iv, 51.

- ibid. ii, 15; iv, 21 ff.; xxiv, 519 ff.

- ibid. xviii, 239.

- ibid. v, 392; xviii, 118.

- Pindar. Nemean Odes x, init.; comp. Aeschylus. Suppliant Maidens, 297.

- Pausanias. Description of Greece ii, 15.5.

- Description of Greece ii, 17, 22; Strabo. Geography, 373; Statius. Thebaid i, 383.

- Description of Greece ii, 24.1 ff; The Library i, 9.28.

- iii, 13.6; 15.7.

- Herod, iii, 60; Description of Greece vii, 4.4; Strabo. Geography, 637.

- Description of Greece ii, 11.2.

- ibid. v, 15.7 ff.

- Thucydides, v, 75; Description of Greece ii, 29.1.

- Description of Greece viii, 26.2.

- Servius on Virgil's Aeneid i, 51.

- Euripides. Helen, 1097.

- Plutarch. Quaestiones Romanae, 74.

- Servius on Virgil's Georgics i, 1.

Sources

- Aken, Dr. A.R.A. van. (1961). Elseviers Mythologische Encyclopedie. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

- Smith, William. (1870). Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology. London: Taylor, Walton, and Maberly.

This article incorporates text from Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology (1870) by William Smith, which is in the public domain.