Zeus

The greatest of the Olympian gods, and the father of gods and men, was a son of Cronus and Rhea, a brother of Poseidon, Hades, Hestia, Demeter, Hera, and at the same time married to his sister Hera. When Zeus and his brothers distributed among themselves the government of the world by lot, Poseidon obtained the sea, Hades the lower world, and Zeus the heavens and the upper regions, but the earth became common to all.1

Later mythologers enumerate three Zeus in their genealogies: two Arcadian ones and one Cretan; and the first is said to be a son of Aether, the second of Coelus, and the third of Saturn.2 This accounts for the fact that some writers use the name of the king of heaven who sends dew, rain, snow, thunder, and lightning for heaven itself in its physical sense.3

According to the Homeric account Zeus, like the other Olympian gods, dwelt on Mount Olympus in Thessaly, which was believed to penetrate with its lofty summit into heaven itself.4 He is called the father of gods and men,5 the most high and powerful among the immortals, whom all others obey.6 He is the highest ruler, who with his counsel manages every thing,7 the founder of kingly power, of law and of order, whence Dike, Themis and Nemesis are his assistants.8

For the same reason he protects the assembly of the people (ἀγοραῖος, agoraios), the meetings of the council (βουλαῖος, boulaios), and as he presides over the whole state, so also over every house and family (ἑρκεῖος, herkeios).9 He also watched over the sanctity of the oath (ὅρκιος, horkios), the law of hospitality (ξένιος, xenios), and protected suppliants (ἱκέσιος, hikesios).10 He avenged those who were wronged, and punished those who had committed a crime, for he watched the doings and sufferings of all men (ἐπόψιος, eposios).11

He was further the original source of all prophetic power, from whom all prophetic signs and sounds proceeded (πανομφαῖος, panomphaios).12 Every thing good as well as bad comes from Zeus, and according to his own choice he assigns their good or evil lot to mortals,13 and fate itself was subordinate to him.

He is armed with thunder and lightning, and the shaking of his aegis produces storm and tempest:14 a number of epithets of Zeus in the Homeric poems describe him as the thunderer, the gatherer of clouds, and the like.

He was married to Hera, by whom he had two sons, Ares and Hephaestus, and one daughter, Hebe.15 Hera sometimes acts as an independent divinity, she is ambitious and rebels against her lord, but she is nevertheless inferior to him, and is punished for her opposition;16 his amours with other goddesses or mortal women are not concealed from her, though they generally rouse her jealousy and revenge.17 During the Trojan war, Zeus, at the request of Thetis favored the Trojans, until Agamemnon made good the wrong he had done to Achilles.

Zeus, no doubt, was originally a god of a portion of nature, whence the oak with its eatable fruit and the fertile doves were sacred to him at Dodona and in Arcadia (hence also rain, storms, and the seasons were regarded as his work, and hence the Cretan stories of milk, honey, and cornucopia); but in the Homeric poems, this primitive character of a personification of certain powers of nature is already effaced to some extent, and the god appears as a political and national divinity, as the king and father of men, as the founder and protector of all institutions hallowed by law, custom, or religion.

Hesiod18 also calls Zeus the son of Cronus and Rhea, and the brother of Hestia, Demeter, Hera, Hades, and Poseidon. Cronus swallowed his children immediately after their birth, but when Rhea was near giving birth to Zeus, she applied to Uranus and Gaea for advice as to how the child might be saved. Before the hour of birth came, Uranus and Gaea sent Rhea to Lyctos in Crete, requesting her to bring up her child there. Rhea accordingly concealed her infant in a cave of Mount Aegaeon, and gave to Cronus a stone wrapped up in cloth, which he swallowed in the belief that it was his son. Other traditions state that Zeus was born and brought up on Mount Dicte or Ida (also the Trojan Ida), Ithome in Messenia, Thebes in Boeotia, Aegion in Achaea, or Olenos in Aetolia. According to the common account, however, Zeus grew up in Crete. As Rhea is sometimes identified with Gaea, Zeus is also called a son of Gaea.19

In the meantime Cronus by a cunning device of Gaea or Metis was made to bring up the children he had swallowed, and first of all the stone, which was afterwards set up by Zeus at Delphi. The young god now delivered the Cyclopes from the bonds with which they had been fettered by Cronus, and they in their gratitude provided him with thunder and lightning. On the advice of Gaea, Zeus also liberated the hundred-armed Hecatonchires — Briareus, Cottus, and Gyges — that they might assist him in his fight against the Titans.20 The Titans were conquered and shut up in Tartarus,21 where they were henceforth guarded by the Hecatonchires. Thereupon Tartarus and Gaea begot Typhon, who began a fearful struggle with Zeus, but was conquered.22

Zeus now obtained the dominion of the world, and chose Metis for his wife.23 When she was pregnant with Athena, he took the child out of her body and concealed it in his own, on the advice of Uranus and Gaea, who told him that thereby he would retain the supremacy of the world. If Metis had given birth to a son, this son (so fate had ordained it) would have acquired the sovereignty. After this Zeus, by his second wife Themis, became the father of the Horae and Moirae; of the Charites by Eurynome, of Persephone by Demeter, of the Muses by Mnemosyne of Apollo and Artemis by Leto, and of Hebe, Ares, and Eileithyia by Hera. Athena was born out of the head of Zeus; while Hera, on the other hand, gave birth to Hephaestus without the co-operation of Zeus.24

The family of the Cronidae accordingly embraces the twelve great gods of Olympus: Zeus (the head of them all), Poseidon, Apollo, Ares, Hermes, Hephaestus, Hestia, Demeter, Hera, Athena, Aphrodite, and Artemis. These twelve Olympian gods, who in some places were worshiped as a body, as at Athens,25 were recognized not only by the Greeks, but were adopted also by the Romans, who, in particular, identified their Jupiter with the Greek Zeus.

In surveying the different local traditions about Zeus, it would seem that originally there were several, at least three, divinities which in their respective countries were supreme, but which in the course of time became united in the minds of the people into one great national divinity. We may accordingly speak of an Arcadian, Dodonaean, Cretan, and a national Hellenic Zeus.

1. The Arcadian Zeus (Ζεὺς Λυκαῖος) was born, according to the legends of the country, in Arcadia, either on Mount Parrhasion,26 or in a district of Mount Lycaeon, which was called Cretea.27 He was brought up there by the nymphs Theisoa, Neda, and Hagno; the first of these gave her name to an Arcadian town, the second to a river, and the third to a well.28Lycaon, a son of Pelasgus, who built the first and most ancient town of Lycosura, called Zeus Lycaeus, and erected a temple and instituted the festival of the Lyceia in honor of him; he further offered to him bloody sacrifices, and among others his own son, in consequence of which he was metamorphosed into a wolf (λύκος, lykos).29 No one was allowed to enter the sanctuary of Zeus Lycaeus on Mount Lycaeon, and there was a belief that, if any one entered it, he died within twelve months after, and that in it neither human beings nor animals cast a shadow.30 Those who entered it intentionally were stoned to death, unless they escaped by flight; and those who had got in by accident were sent to Eleutherae.31 On the highest summit of Lycaeon, there was an altar of Zeus, in front of which, towards the east, there were two pillars bearing golden eagles. The sacrifices offered there were kept secret.32

2. The Dodonaean Zeus (Ζεὺς Δωδωναῖος or Πελασγικό) possessed the most ancient oracle in Greece, at Dodona in Epeirus, near Mount Tomarus (Tmarus or Tomurus), from which he derived his name.33 At Dodona Zeus was mainly a prophetic god, and the oak tree was sacred to him; but there too he was said to have been reared by the Dodonaean nymphs.34

3. The Cretan Zeus (Ζεὺς Δικταῖος or Κρηταγενής). We have already given the account of him which is contained in the Theogony of Hesiod. He is the god, to whom Rhea, concealed from Cronus, gave birth in a cave of Mount Dicte, and whom she entrusted to the Curetes and the nymphs Adrasteia and Ide, the daughters of Melisseus. They fed him with milk of the goat Amalthea and the bees of the mountain provided him with honey.35Crete is called the island or nurse of the great Zeus, and his worship there appears to have been very ancient.36 Among the places in the island which were particularly sacred to the god, we must mention the district about Mount Ida, especially Cnosus, which was said to have been built by the Curetes, and where Minos had ruled and conversed with Zeus;37 Gortyn, where the god, in the form of a bull, landed when he had carried off Europa from Phoenicia, and where he was worshiped under the surname of Hecatombaeus;38 further the towns about Mount Dicte, as Lyctos,39 Praesos, Hierapytna, Biennos, Eleuthernae and Oaxus.40

4. The national Hellenic Zeus, near whose temple at Olympia in Elis, the great national πανήγυρις (panēgyris) was celebrated every fifth year. There too Zeus was regarded as the father and king of gods and men, and as the supreme god of the Hellenic nation. His statue there was executed by Phidias, a few years before the outbreak of the Peloponnesian war, the majestic and sublime idea for this statue having been suggested to the artist by the words of Homer.41 According to the traditions of Elis, Cronus was the first ruler of the country, and in the golden age there was a temple dedicated to him at Olympia. Rhea, it is further said, entrusted the infant Zeus to the Idaean Dactyls, who were also called Curetes, and had come from Mount Ida in Crete to Elis. Heracles, one of them, contended with his brother Dactyls in a footrace, and adorned the victor with a wreath of olive. In this manner he is said to have founded the Olympian games, and Zeus to have contended with Cronus for the kingdom of Elis.42

The Greek and Latin poets give to Zeus an immense number of epithets and surnames, which are derived partly from the places where he was worshiped, and partly from his powers and functions. He was worshiped throughout Greece and her colonies, so that it would be useless and almost impossible to enumerate all the places.

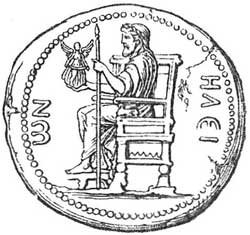

The eagle, the oak, and the summits of mountains were sacred to him, and his sacrifices generally consisted of goats, bulls and cows.43 His usual attributes are the scepter, eagle, thunderbolt, and a figure of Victory in his hand, and sometimes also a cornucopia. The Olympian Zeus sometimes wears a wreath of olive, and the Dodonaean Zeus a wreath of oak leaves.

❧

Iconography

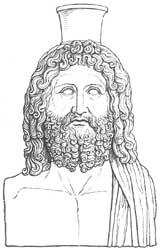

In works of art Zeus is generally represented as the omnipotent father and king of gods and men, according to the idea which had been embodied in the statue of the Olympian Zeus by Phidias. He is portrayed as a majestic figure with long hair and a beard, initially in the nude but later often fully clothed. The eagle and the lightning bolt are his attributes, as well as a globe and a scepter. He is depicted uncountable times in the most varying functions and connected to almost all major Greek myths and legends. Most famous was his statue at Olympia, created by Phidias. It was made of gold and ivory and depicted Zeus in a seated position. Among the existing statues is the bust by Otricoli in the Vatican Museum: his noble features make him appear calm, regal, and benign.

References

Notes

- Homer. Iliad xv, 187, ff.; i, 528; ii, 111; Virgil. Aeneid iv, 372.

- Cicero. On the Nature of the Gods iii, 21.

- Horace. Carmina i, 1.25; Virgil. Georgics ii, 419.

- Homer. Iliad i, 221 ff., 354, 609; xxi, 438.

- ibid. i, 514; v, 33; comp. Aeschylus. Seven Against Thebes, 512.

- Iliad xix, 258; viii, 10 ff.

- ibid. i, 175; viii, 22.

- ibid. i, 238; ii, 205; ix, 99; xvi, 387; comp. Hesiod. Works and Days, 36; Callimachus. Hymn to Jupiter, 79.

- Homer. Odyssey xxii, 335; comp. Ovid. Ibis, 285.

- Odyssey ix, 270; comp. Pausanias. Description of Greece v, 24.2.

- Odyssey xiii, 213; comp. Apollonius Rhodius. The Library i, 1123.

- Iliad viii, 250; comp. Aeschylus. Eumenides, 19; Callimachus. Hymn to Jupiter, 69.

- Odyssey iv, 237; vi, 188; ix, 552; Iliad x, 71; xvii, 632 ff.

- Iliad xvii, 593.

- Iliad i, 585; v, 896; Odyssey xi, 604.

- Iliad xv, 17 ff.; xix, 95 ff.

- ibid. xiv, 317.

- Theogony, 116 ff.

- Aeschylus. Suppliant Maidens, 901.

- Pseudo-Apollodorus. The Library i, 2.1; Hesiod. Theogony, 617 ff.

- Hesiod. Theogony, 717.

- ibid., 820, ff.

- ibid., 881, ff.

- ibid., 886, ff.

- Thucydides, vi, 54.

- Callimachus. Hymn to Jupiter, 7, 10.

- Pausanias. Description of Greece viii, 38.1; Callimachus, l.c., 14.

- Description of Greece viii, 38.2 ff.; 47.2; comp. Callimachus, l.c., 33.

- Description of Greece viii, 2.1, 38.1; Callimachus, l.c., 4; Ovid. Metamorphoses i, 218.

- Description of Greece viii, 38.5; comp. Scholiast on Callimuchus' Hymn to Jupiter, 13.

- Plutarch. Greek Questions, 39.

- Pausanias. Description of Greece viii, 38.5; Callimachus, l.c., 68.

- Homer. Iliad ii, 750; xvi, 233; Herod, ii, 52; Pausanias. Description of Greece i, 17.5; Strabo. Geography v, 338; vi, 504; Virgil. Eclogues viii, 44.

- Hyades; Scholiast on Homer's Iliad xviii, 486; Hyginus. Fabulae, 182; Ovid. Fasti vi, 711; Metamorphoses iii, 314.

- Pseudo-Apollodorus. The Library i, 1.6; Callimachus, l.c.; Diodorus Siculus, v, 70; comp. Athenaeus, xi, 70; Fasti v, 115.

- Virgil. Aeneid iii, 104; Dionysius Periegetes, 501.

- Homer. Odyssey xix, 172; Plato. De Legibus i, 1; Diodorus Siculus, v, 70; Strabo. Geography x, 730; Cicero. On the Nature of the Gods iii, 21.

- Hesychius, s.v.

- Hesiod. Theogony, 477.

- Comp. Hoeck. Creta i, 160 ff.; 339 ff.

- Homer. Iliad i, 527. Comp. Hyginus. Fabulae, 223.

- Pausanias. Description of Greece v, 7.4.

- Homer. Iliad ii, 403; Aristotle Ethics v, 10; ix, 2; Virgil. Aeneid iii, 21; ix, 627.

Source

- Smith, William. (1870). Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology. London: Taylor, Walton, and Maberly.

This article incorporates text from Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology (1870) by William Smith, which is in the public domain.